Principles Of Periodontal Instrumentation Including Scaling And Rood Planing

Question 1. Write short note on sharpening of periodontal instruments.

Or

Write short note on principles of sharpening of instruments.

Answer. Instruments are sharpened to produce a functionally sharpened edge to preserve the shape and contour of instrument.

Objectives of Sharpening

- To improve control of operator over the instrument.

- To reduce to working time.

- To reduce the burnishing of calculus.

- To reduce grooving or nicking of root surface.

- To improve tactile sensitivity.

- To decrease the fatigue and stress of clinician.

Types of Sharpening Stones

- Sharpening stones from natural mineral deposits and produced artificially

- Natural abrasive stones: Arkansas oil stones, India stone

- Synthetically produced stone: Carborundum, ruby and ceramic stone

Read And Learn More: Periodontics Question And Answers

- Sharpening stones can be categorized on their method of use:

- Mounted rotary stones: They are mounted on motor mandrel and are driven by motor. They may be cylindrical, conical and disc shaped. Not recommended for routine use.

- Unmounted stones: They are available in variety of size and shapes, e.g. rectangular with flat or grooved surfaces, cylindrical or cone shaped.

Principles of Sharpening

- Choose a suitable sterilized sharpening stone of appropriate shape and abrasiveness for the instrument sharpening.

- Establish the proper angle between the sharpening stone and the surface of the instrument.

- Maintain a stable, firm grasp of both the instrument and the sharpening stone. This ensures that the proper angulation is maintained throughout the controlled sharpening stroke.

- Avoid excessive pressure. Excessive pressure causes the stone to grind the surface of the instrument more quickly and may shorten the instrument’s life

- Avoid the formation of “wire-edge”. Characterized by minute filamentous projections of metal extending as a rounded ledge from the sharpened cutting edge.

- Lubricate the stone during sharpening this minimizes clogging of the abrasive surface of the sharpening stone with metal particles removed from the instrument. Oil should be used for natural stones and water for synthetic stones.

- Sharpen instruments during first sign of dullness. A grossly dull instrument requires the removal of great deal of metal to produce a sharp-cutting edge, which shortens the effective life of instrument.

Evaluation of Sharpness

Sharpness can be evaluated by sight and touch.

- When a dull instrument is held under a light, the rounded surface of its cutting edge reflects light back. The acuteangled cutting edge of a sharp instrument, has no surface area to reflect light. No bright line can be observed.

- Tactile sensation by drawing the instrument lightly across an acrylic rod known as a “Sharpening test stick”. Dull instrument will slide smoothly.

Question 2. Write short note on instrument stabilization.

Or

Describe various instrument grasps and finger rests.

Answer. Stability of the instrument and the hand is the primary requisite for controlled instrumentation.

- Stability and control is essential for effective instrumentation and to avoid injury to the patient or clinician.

- The two factors that provide stability are, instrument grasp and finger rest.

Instrument Grasp

- A proper grasp is essential for precise control of movements made during periodontal instrumentation.

- The most effective and stable grasp for all periodontal instruments is modified pen grasp. This grasp allows precise control to the working end, permits a wide range of movements and facilitates good tactile conduction.

- The palm and thumb grasp is useful for stabilizing instruments during sharpening and for manipulating air-water syringes.

Finger Rest

- The finger rest serves to stabilize the hand and the instrument by providing a firm fulcrum, as movements are made to activate the instrument.

- A good finger rest prevents injury and laceration of the gingival and surrounding tissues.

- The ring finger is preferred by most clinicians for the finger rest. Maximal control is achieved when the middle finger is kept between the instrument shank and the fourth finger. This built-up fulcrum is an integral part of the wristforearm action that activates the powerful working stroke for calculus removal.

- Finger rests may be generally classified as intraoral finger rests or extraoral fulcrums.

- The standard intraoral finger rest generally rest on stable tooth surface immediately adjacent to working area.

- Following are the advanced intraoral finger rests

- Modified intra-oral fulcrum: Achieved by combining an altered modified pen grasp with standard intra-oral fulcrum

- Piggy-backed fulcrum: Middle finger rest on top of ring finger.

- Cross-arched fulcrum: Accomplish by resting a ring finger on tooth on opposite side of arch from teeth being instrumented.

- Opposite arch fulcrum: Accomplished by resting the ring finger on the opposite arch.

- Finger-on-finger fulcrum: Accomplished by resting the ring finger on index finger.

- Basic extraoral fulcrums are

- Palm up technique: Clinician rest the Knuckle against patient’s chin or cheek

- Palm down technique: Clinician cups the patient’s chin with palm of the hand.

Question 3. Write in detail about principles of periodontal instrumentation.

Or

Explain principles of periodontal instrumentation.

Or

Write short note on periodontal instrumentation.

Answer. Following are the principles of periodontal instrumentation

- Accessibility

- Visibility, illumination and retraction

- Condition of instruments

- Maintaining a clean field

- Instrument stabilization

- Instrument activation

Accessibility

- It is generally related to the position of the patient and operator.

- It facilitates thoroughness of instrumentation. The position of the patient and operator should provide maximal accessibility to the area of operation.

- Inadequate accessibility impedes thorough instrumentation, prematurely tires the operator, and diminishes his or her effectiveness.

Neutral Seated Position for the Clinician

- Forearm parallel to the floor.

- Weight evenly balanced.

- Thighs parallel to the floor.

- Hip angle of 90°.

- Seat height positioned low enough so that the heels of your feet touch the floor.

- When working from clock positions 9–12:00, spread feet apart so that your legs and the chair base form a tripod which creates a stable position.

- Avoid positioning your legs under the back of the patient’s chair.

- Back straight and the head erect.

Patient’s Position

- Patient should be in a supine position and placed in such a way that the mouth is close to the resting elbow of the clinician.

- Body: Patient’s heel should be slightly higher than the tip of his or her nose. The back of the chair should be nearly parallel to the floor for maxillary treatment areas.

- Chair back may be raised slightly for mandibular treatment areas.

- Head: The foremost of the patient’s head should be even with the upper edge of the head rest.

- For mandibular areas–chin down position.

- Maxillary areas-chin up position.

- Head rest: If the head rest is adjustable, it should be raised or lowered, so that the patient’s neck and head are aligned with the torso.

Visibility, Illumination and Retraction

Visibility

Whenever possible, direct vision with direct illumination from the dental light is most desirable. If this is not possible, indirect vision may be obtained by using a mouth mirror to reflect light where it is needed.

Dental Mirror

It is a hand instrument which has a reflecting mirror surface used to view tooth surfaces that cannot be seen by direct vision.

Transillumination

When transilluminating a tooth, the mirror is used to reflect light through the tooth surface. The transilluminated tooth almost will appear to glow. It is effective only with anterior teeth because they are thin enough to allow the light to pass through them.

- Procedure:

- Step 1: Position yourself in l2 o’ clock position.

- Step 2: Using a modified pen grasp, hold the mirror in the non-dominant hand. Bring the arm up and over the patient’s face. Gently rest your ring finger on the side of the patient’s lip or cheek.

- Step 3: Hold the dental mirror behind the central incisors so that the reflecting surface is parallel to the lingual surface. Position the unit light so that the light beam shines on the dental mirror at a 90° angle to the mirrors reflecting surfaces.

- Step 4: Properly positioned light and the mirror will result in glow.

Retraction

It provides visibility, accessibility and illumination. The following methods are effective for retraction:

- Use of the mirror to deflect the cheek while the fingers of the non-operating hand retract the lips and protect the angle of the mouth from irritation by the mirror handle.

- Use of the mirror alone to retract the lips and cheek.

- Use of fingers of the non-operating hand to retract the lips.

- Use of the mirror to retract the tongue.

- Combination of the preceding methods.

Condition of Instruments (Sharpness)

Prior to any instrumentation, all instruments should be inspected to make sure that they are clean, sterile and in good condition. The working ends of pointed or bladed instruments must be sharp to be effective.

- Advantages of sharpness

- Easier calculus removal.

- Improved stroke control.

- Reduced number of strokes.

- Increased patient comfort.

- Reduced clinician fatigue.

Ideally, it is best to sharpen your instruments after autoclaving and then reautoclave them prior to patient treatment. Dull instruments may lead to incomplete calculus removal and unnecessary trauma because of excess force applied.

Maintaining a Clean Field

- Despite good visibility, illumination and retraction, instrumentation can be hampered, if the operative field is obscured by saliva, blood and debris.

- Adequate suction is essential and can be achieved with a saliva ejector or, an aspirator.

- Blood and debris can be removed from the operative field with suction and by wiping or blotting with gauze squares.

- The operative field should also be flushed occasionally with water.

- Compressed air and gauze square can be used to facilitate visual inspection of tooth surfaces just below the gingival margin during instrumentation.

- Retractable tissue can also be deflected away from the tooth by gently packing the edge of gauze square into the pocket with the back of a curette.

Instrument Stabilization

- Stability of the instrument and the hand is the primary requisite for controlled instrumentation. Stability and control is essential for effective instrumentation and to avoid injury to the patient or clinician. The two factors that provide stability are instrument grasp and finger rest.

- Instrument Grasp

- A proper grasp is essential for precise control of movements made during periodontal instrumentation.

- The most effective and stable grasp for all periodontal instruments is modified pen grasp. This grasp allows precise control to the working end, permits a wide range of movements and facilitates good tactile conduction.

- The palm and thumb grasp is useful for stabilizing instruments during sharpening and for manipulating air-water syringes.

Finger Rest

- Finger rest serves to stabilize the hand and the instrument by providing a firm fulcrum, as movements are made to activate the instrument.

- A good finger rest prevents injury and laceration of the gingival and surrounding tissues.

- The ring finger is preferred by most clinicians for the finger rest. Maximal control is achieved when the middle finger is kept between the instrument shank and the fourth finger. This built-up fulcrum is an integral part of the wrist forearm action that activates the powerful working stroke for calculus removal.

- Finger rests may be generally classified as intraoral finger rests or extraoral fulcrums.

- The standard intraoral finger rest generally rest on stable tooth surface immediately adjacent to working area.

- Following are the advanced intraoral finger rests

- Modified intra-oral fulcrum: Achieved by combining an altered modified pen grasp with standard intra-oral fulcrum

- Piggy-backed fulcrum: Middle finger rest on top of ring finger.

- Cross-arched fulcrum: Accomplish by resting a ring finger on tooth on opposite side of arch from teeth being instrumented.

- Opposite arch fulcrum: Accomplished by resting the ring finger on the opposite arch.

- Finger-on-finger fulcrum: Accomplished by resting the ring finger on index finger.

- Basic extraoral fulcrums are

- Palm up technique: Clinician rest the Knuckle against patient’s chin or cheek

- Palm down technique: Clinician cups the patient’s chin with palm of the hand.

Instrument Activation

Following are the points to be considered:

- Adaptation

- Angulation

- Lateral pressure

- Strokes

Adaptation

It refers to the manner in which the working end of a periodontal instrument is placed against the surface of the tooth. The objective of adaptation is to make the working end of the instrument confirm to the contour of the tooth surface.

The cutting edge has three imaginary sections:

- Leading third-used more often during instrumentation.

- Middle third.

- Heel third.

Precise adaptation must be maintained with all instruments to avoid trauma to the soft tissues and root surfaces and to ensure maximum effectiveness of instrumentation. Bladed instruments such as curette and sharp-pointed instruments such as explorers are more difficult to adapt.

Angulation

It refers to the angle between the face of a bladed instrument and the tooth surface.

- For insertion beneath the gingival margin, the face to tooth surface angulation should be an angle between 0 to 40°.

- For calculus removal, angulation should be between 45 to 90°. The exact blade angulation depends on the amount and nature of calculus, the procedure being performed and condition of tissue during scaling or root planning, with angulation of less than 45°, the cutting edge will slide over the calculus smoothening or burnishing it. When gingival curettage is indicated, angulation greater than 90° is deliberately established.

Lateral Pressure

- It refers to the pressure created when force is applied against the surface of a tooth with the cutting edge of a bladed instrument. Exact amount of pressure depends upon the procedure performed. It may be firm, moderate or light when insufficient lateral pressure is applied on rough ledges or lumps may be shaved to thin, smooth sheets of burnished calculus.

- Repeated application of excessively heavy strokes will nick or gouge the root surface. The careful application of varied and controlled amounts of lateral pressure during instrumentation is an integral part of effective scaling and root planning techniques.

Strokes

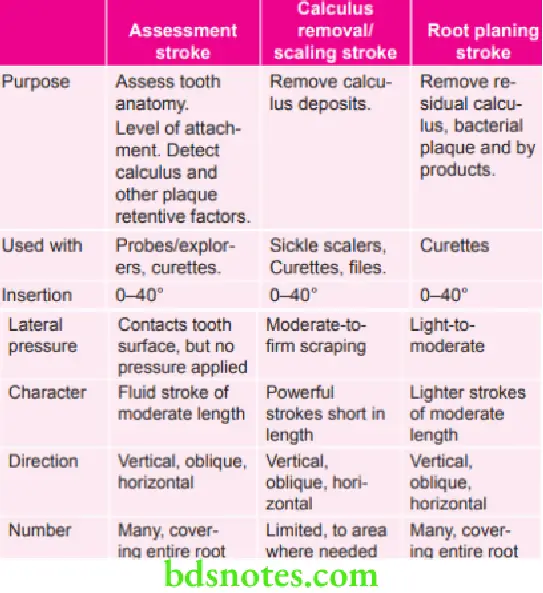

There are four types of strokes:

- Placement stroke.

- Exploratory stroke or assessment stroke.

- Scaling stroke.

- Root planning stroke.

The placement stroke is used to position the working end of an instrument apical to a calculus deposit or at the base of a sulcus or pocket.

Question 4. What are the criteria for judging that your instrument (that you have sharpened) is perfect for the procedure. Explain wire-edge.

Answer. Sharpness can be evaluated by sight and touch in following ways:

- When a dull instrument is held under a light, the rounded surface of its cutting edge reflects light back to the observer. It appears as a bright line running the length of the cutting edge. The acutely angled cutting edge of a sharp instrument, on the other hand, has no surface area to reflect light. When a sharp instrument is held under a light no bright line can be observed.

- Tactile evaluation of sharpness is performed by drawing the instrument lightly across an acrylic rod known as “sharpening test stick.” A dull instrument will slide smoothly, without “biting” into the surface and raising a light shaving as a sharp instrument would.

Wire-edge

- A wire-edge is produced when the direction of the sharpening stroke is away from, rather than into or toward the cutting edge.

- Avoid the formation of a wire edge characterized by minute filamentous projections of metal extended as a roughened ledge from the sharpened cutting edge. When the instrument is used on the root surfaces these projections produced a groove surface rather than a smooth surface.

- When back and forth or up and down sharpening strokes are used formation of a wire edge can be avoided by finishing with a down stroke towards the cutting edge.

Question 5. Write indications, contraindications and objectives of scaling and root planning.

Answer. Scaling and root planning remove bacterial plaque and calculus which are responsible for causing gingival inflammation.

Indications

- For removing heavy tenacious calculus and stains.

- In overhanging margins of amalgam restorations.

- In orthodontic cement removal

Contraindications

- In patients with a pacemaker, electromagnetic sound waves from ultrasonic unit can interfere with electronic function of pacemaker.

- In children, vibrations can cause damage to growing tissues.

- In patients with contagious diseases such as hepatitis, tuberculosis, as these microorganisms spread through water spray.

- In local osteomyelitis.

- In uncontrolled diabetes.

- In chronic nutritional deficiencies.

- In local metastatic neoplasms.

- In patients on prolonged antibiotics and steroid therapy.

Objectives

Primary objectives of scaling and root planning are:

- Restoration of gingival health achieved by complete removal of dental plaque and calculus and converting inflamed bleeding or suppurating pathological pockets to healthy gingival tissue.

- To suppress or eliminate the pathogenic periodontal microflora and replacing with healthy microflora.

- To facilitate shrinkage of the deepened pathologic pocket to a shallow and healthy gingival sulcus.

- To provide a root surface compatible with re-establishment of a healthy connective tissue and epithelial attachment.

Question 6. Write short note on scaling and root planing.

Answer. Scaling is the process by which biofilm and calculus are removed from both supragingival and subgingival tooth surfaces. No deliberate attempt is made to remove tooth substance along with the calculus.

Root planing is the process by which residual embedded calculus and portions of cementum are removed from the roots to produce a smooth, hard, clean surface.

The primary objective of scaling and root planing is to restore gingival health by completely removing elements that provoke gingival inflammation (i.e., biofilm, calculus, and endotoxin) from the tooth surface.

Scaling and root planing are not separate procedures; all the principles of scaling apply equally to root planing. The difference between scaling and root planing is only a matter of degree. The nature of the tooth surface determines the degree to which the surface must be scaled or planed.

Deposits of calculus are frequently embedded in cemental irregularities; therefore scaling alone is insufficient, and a portion of the root surface must be removed to eliminate these deposits.

Supragingival Scaling

- It is done coronal to the gingival margin which allows direct visibility and freedom of movement. This makes adaptation and angulation of instruments much easier as compared to subgingival scaling and root planing.

Instruments

Sickle scalers, curettes and ultrasonic and sonic instruments are most commonly used during supragingival scaling.

Technique

Following are the steps to be followed during supragingival scaling:

- Grasp: Supragingival scaling is performed with sickle scaler or curette by holding them with a modified pen grasp.

- Finger rest: A firm finger rest is achieved on the teeth adjacent to working area.

- Adaptation and angulation: The blade is adapted with an angulation of slightly less than 90° to surface being scaled. Sharply pointed tip of sickle can easily lacerate marginal tissue or gouge exposed root surfaces, so careful adaptation is especially important when this instrument is being used.

- Strokes: The Cutting edge of blade should engage the apical margin of supragingival calculus. Short, powerful and overlapping scaling strokes should be activated coronally in a vertical or oblique direction.

- Endpoint: Final scaling should always follow with the finishing curette. The tooth surface is needed to be instrumented till it appears visually and tactilely free of all supragingival deposits.

Subgingival Scaling and Root Planing

It is performed apical to the gingiva which impairs the visibility and freedom of movement. Visibility is also obscured by the bleeding which is inevitable during subgingival instrumentation. Adaptation and angulation of the instruments are more during subgingival scaling and root planing. However subgingival calculus is harder when compared to supragingival calculus and is fixed into root irregularities which make it more tenacious and hard to remove.

Instruments

Subgingival scaling and root planing are commonly performed with either universal or area-specific (Gracey) curettes, Sickles, hoes, Hirschfeld files and thin ultrasonic tips may also be useful for the removal of subgingival calculus.

Technique

Following are the steps to be followed during subgingival scaling:

- Grasp: A modified pen grasp is used to hold curette.

- Finger rest: A stable finger rest is established on the teeth adjacent to the working area. Location of the finger rest or fulcrum is important to keep lower shank of instrument to be parallel or nearly parallel to the tooth surface which is being treated and to enable the operator to use wrist-arm motion. Finger rest must be close enough to working area to fulfill these two requirements, except in some aspects of the maxillary posterior teeth, where these requirements can be met only with the use of extraoral or opposite-arch fulcrums.

- Insertion: The blade is inserted under the gingiva at 0°.

- Adaptation and angulation: The correct cutting edge should be adapted to the tooth, and the lower shank is kept parallel to the tooth surface with the face of blade nearly flush with the tooth surface. With the entry of cutting edge at base of the pocket, a working angulation is maintained between 45° and 90°, and pressure is applied laterally against the tooth surface.

- Strokes: Calculus is removed by a series of controlled, overlapping, short and powerful strokes primarily using wrist-arm motion. Longer, lighter root planing strokes are then activated with less lateral pressure until the root surface is completely smooth and hard. The instrument handle must be rolled carefully between the thumb and the fingers to keep the blade adapted closely to the tooth surface as line angles and developmental depressions in tooth contour are followed. During scaling strokes, force should be maximized by concentrating lateral pressure onto the lower third of blade. This small section, the terminal few millimeters of the blade, is positioned slightly apical to the lateral edge of the deposit, and a short vertical or oblique stroke is used to split the calculus from the tooth surface. Without withdrawing the instrument from the pocket, the lower third of the blade is advanced laterally and repositioned to engage the next portion of remaining deposit. Another vertical or oblique stroke is made, slightly overlapping the previous stroke. This process is repeated in a series of powerful scaling strokes until the entire deposit has been removed. The overlapping of these pathways or “channels” of instrumentation ensures that the entire instrumentation zone is covered.

- Endpoint: Final subgingival scaling and root planning should always follow with the finishing curette. The tooth surface is instrumented until all subgingival deposits are removed.

Leave a Reply