Haemorrhage, Shock and Blood Transfusion Haemorrhage Classification

1. Depending on the nature of the vessel involved

- Arterial haemorrhage: Bright red in colour, jets out. Pulsation of the artery can be seen. It can be easily controlled, as it is visible.

- Venous haemorrhage: Dark red in colour. It never gets out but oozes out. Difficult to control because the vein gets retracted, nonpulsatile.

- Capillary haemorrhage: Red colour, never jets out, slowly oozes out. It becomes significant if there are bleeding tendencies.

Read And Learn More: Clinical Medicine And Surgery Notes

2. Depending on the timing of haemorrhage

- Primary haemorrhage: Occurs at the time of surgery

- Reactionary haemorrhage: Occurs after 6–12 hours of surgery. Hypertension in the postoperative period, violent sneezing, coughing or retching, are the usual causes, for example. superior thyroid artery can bleed postoperatively if ligature slips. Hence, it is better to ligate it twice.

- Secondary haemorrhage: Occurs after 5–7 days of surgery. It is due to infection which eats away the suture material, causing sloughing of the vessel wall, e.g. bleeding after 5–7 days of surgery for haemorrhoids.

3. Depending on the duration of the haemorrhage

- Acute haemorrhage: Occurs suddenly, for example. oesophageal variceal bleeding due to portal hypertension.

- Chronic haemorrhage: Occurs over a period of time, for example. haemorrhoids/piles or chronic duodenal ulcer, tuberculous ulcer of the ileum, diverticular disease of the colon.

4. Depending on the nature of bleeding

External haemorrhage/Revealed haemorrhage, for example. epistaxis, haematemesis

Internal haemorrhage/Concealed haemorrhage, for example. splenic rupture following injury, ruptured ectopic gestation, liver laceration following injury

Haemorrhagic Shock

A loss of more than 30–40% in blood volume results in a fall in blood pressure and gross hypoperfusion of the tissues leading to haemorrhagic shock.

The evolution of haemorrhagic shock can be classified into four stages:

Haemorrhagic Shock Class 1

- When blood loss is less than 750 ml (<15 % of blood volume), it can be called mild haemorrhage.

- 60–70% of blood volume is present in the low-pressure venous system (capacitance vessels). 10% of the blood volume is present in the splanchnic circulation.

- When there is blood loss, peripheral vasoconstriction takes place and compensates for the loss of blood volume by shifting some blood into the central circulation. Some amount of correction of blood volume also occurs due to the withdrawal of fluid from the interstitial spaces.

- Apart from mild tachycardia and thirst, there may be no other symptom or sign suggesting hypovolaemia. The blood pressure, urine output and mentation are all normal in Class 1 shock.

Haemorrhagic Shock Class 2

- Loss of 800–1500 ml (15–30% of blood volume) results in moderate (Class II) shock.

- Peripheral vasoconstriction may not be sufficient to maintain circulation. Hence, adrenaline and noradrenaline (catecholamines) released from the sympatho-adrenal system cause powerful vasoconstriction of both arteries and veins.

- Increased secretion of ADH causes retention of water and salt. Thirst increases.

- Clinically, the patient shows a heart rate of 100–120 beats/minute and an elevated diastolic pressure. The systolic pressure may remain normal. Urine output is reduced to about 0.5 ml/kg/h and the capillary refill is more than the normal 2 seconds. Extremities may look pale and the patient is confused and thirsty.

Haemorrhagic Shock Class 3

- Loss of 1500–2000 ml (30–40% of blood volume) produces Class III shock. All the signs and symptoms of Class II haemorrhage get worse.

- The patient’s systolic and diastolic blood pressures fall, and the heart rate increases to around 120 beats/minute. The pulse is ready.

- The respiratory rate increases to more than 20/minute. Urine output drops to 10 to 20 ml/hour. The patient appears pale and is aggressive, drowsy or confused.

Haemorrhagic Shock Class 4

- A blood loss of more than 2000 ml (> 40% of blood volume) results in Class IV shock. The peripheries are cold and ashen. The pulse is thready and more than 120/ minute. The blood pressure is very low or

- unrecordable.

- There may be renal shutdown and the patient may be moribund.

- If persistent, can damage other organs, for example

Git: Mucosal ulcerations, upper GI bleeding, absorption of bacteria and toxins, bacterial translocation and bacteraemia

Liver: Reduced clearance of toxins

Kidney: Acute renal failure

Heart: Myocardial ischaemia, depression

Lungs: Loss of surfactant, increased alveolocapillary permeability, interstitial oedema, and increased arteriovenous shunting results in acute lung injury (ALI). These result in multiorgan failure associated with a high mortality rate. The only hope of survival is early diagnosis of bleeding and appropriate management.

Haemorrhagic Shock Management

Treatment of the shock—General measures

- Hospitalisation

- Care of all critically ill patients starts with A, B and C. A-Airway, B-Breathing and C Circulation.

- Oxygen should be administered by facemask for all patients who are in shock but are conscious and are able to maintain their airways.

- If unconscious, endotracheal intubation and ventilation with oxygen may be necessary.

- Intravenous line: Urgent intravenous administration of isotonic saline to restore the blood volume to normal. Colloids such as gelatins or hetastarch have also been used. If there has been massive blood loss as in Class IV shock or the patient is anaemic, blood transfusion is indicated.

- Investigations: Blood is collected at the earliest opportunity for routine investigations as well as for blood grouping and cross-matching

- Cross-matched blood is usually given. When life-threatening, uncross-matched, O -ve O-packed cells may be transfused into the patient.

- If started, they should be terminated as soon as the volume status is corrected.

Treatment of the shock—Specific measures

1. Pressure and packing

- To control bleeding from the nose, and scalp: pack using roller gauze with or without adrenaline to control bleeding from the nose.

- Bleeding from vein—the middle thyroid vein during thyroidectomy, and lumbar veins during lumbar sympathectomy can be controlled using a pressure pack for a few minutes.

- Sengstaken tube is used to control bleeding from oesophageal varices-internal tamponade.

2. Position and rest

- Elevation of the leg controls bleeding from varicose veins.

- Elevation of the head end reduces venous bleeding in thyroidectomy— Anti-Trendelenberg position.

- Sedation to relieve anxiety—Morphine in titrated doses of 1–2 mg intravenously.

Management Tourniquets

Management Indications

- Reduction of fractures

- Repair of tendons

- Repair of nerves

- When a bloodless field is desired during surgery.

Management Contraindications

Patient with peripheral vascular disease. (The arterial disease may be aggravated due to thrombosis resulting in gangrene.)

Management Tourniquets Types

- Pneumatic cuffs with pressure gauge

- Rubber bandage.

Management Precautions

- Too loose a tourniquet does not serve the purpose.

- Too tight: Arterial thrombosis can occur which may result in gangrene.

- Too long (duration of application): Gangrene of the limb. Hence, when a tourniquet is applied, the time of inflation should be noted down and at the end of 45 minutes to an hour, deflated at least for 10 minutes and reinflated only if necessary

Management Complications

- Ischaemia and gangrene

- Tourniquet nerve palsy1

4. Surgical methods to control haemorrhage:

- Application of artery forceps (Spencer Well’s forceps) to control bleeding from veins, arteries and capillaries.

- Application of ligatures for bleeding vessels

- Cauterisation (diathermy)

- Application of bone wax (Horsley’s wax which is bee’s wax in almond oil) to control bleeding from cut edges of bones.

- Silver clips are used to control bleeding from cerebral vessels (Cushing’s clip).

- Surgical procedure: Splenectomy for splenic rupture, hysterectomy for uncontrollable postpartum haemorrhage, laparotomy for control of bleeding from ruptured ectopic pregnancy, etc.

Shock Definition

Shock is defined as an acute clinical syndrome characterised by hypoperfusion and severe dysfunction of vital organs. There is a failure of the circulatory system to supply blood in sufficient quantities or under sufficient pressure necessary for the optimal function of organs vital to survival.

Shock Classification

- Hypovolaemic shock

- Cardiogenic shock

- Distributive shock

- Obstructive shock

Hypovolaemic Shock

- Loss of blood—haemorrhagic shock

- Loss of plasma—as in burns shock

- Loss of fluid — dehydration as in gastroenteritis

Hypovolaemic Shock Features

- The primary problem is a decrease in preload. The decreased preload causes a decrease in stroke volume.

- Clinical features depend on the degree of hypovolaemia. Severe (Class 3 or 5) shock results in tachycardia, low blood pressure and decreased urine output.

- The peripheries are cold and the patient may be confused or moribund.

Hypovolaemic Shock Treatment

- The primary goal is to return the blood volume, tissue perfusion and oxygenation to normal as early as possible.

- Replace the lost blood volume

- Crystalloids: 2–3 times the volume of blood lost must be replaced with isotonic saline (0.9% saline) or Ringer lactate. Large volumes of saline infusion can cause hyperchloraemic metabolic acidosis. 5% dextrose does not produce expansion of intravascular volume as it gets distributed throughout the different fluid compartments.

Hypovolaemic Shock

Decreased preload

↓

Decrease in stroke volume

↓

Sympathetic nervous system activation

In the MS examination, a candidate was asked to examine a case of radial nerve palsy. Patient had an injury to the wrist 4 months back. The cut flexor tendons had been sutured. The candidate could not correlate the radial nerve palsy to the injury at the wrist. He failed! It was a case of tourniquet palsy.

- Colloids: 1–1.5 times the blood lost can be replaced with colloid instead of crystalloid (5% albumin, gelatin or hetastarch).

- Blood transfusion may be needed if large amounts of blood are lost (Hb < 8–10 gm%) or if the patient is anaemic.

Cardiogenic Shock

The blood flow is reduced because of an intrinsic problem in the heart muscle or its valves. A massive myocardial infarction may damage the cardiac muscle so that there is not much healthy muscle to pump blood effectively. Any damage to the valves, especially acute may also reduce the forward cardiac output resulting in cardiogenic shock.

Cardiogenic Shock Features

- The primary problem is a decrease in contractility of the heart. The decreased contractility causes a decrease in stroke volume.

- Left ventricular pressures are high as forward cardiac output suffers. The sympathetic nervous system is activated and consequently, systemic vascular resistance increases.

- Clinically, the patient presents with tachycardia, low blood pressure and decreased urine output.

- The jugular venous pulse may be raised, a S3 or S4 gallop may be present.

- The lung fields may show bilateral extensive crepitations due to pulmonary oedema.

- The peripheries are cold and the patient may be confused or moribund.

Cardiogenic Shock Treatment

- The primary goal is to improve cardiac muscle function.

- Oxygenation can be improved by administering oxygen, either by facemask or by endotracheal intubation and ventilation as necessary.

- Inotropes: improve cardiac muscle contractility.

- Vasodilators such as nitroglycerine may dilate the coronary arteries and peripheral vessels to improve tissue perfusion. High systemic vascular resistance increases impedance to forward cardiac output (afterload). However, the patient must be monitored closely to avoid excessive drops in blood pressure due to these drugs.

- Intra-aortic balloon pump or ventricular assist devices may be used to help the ventricles. If unresponsive, revascularisation (surgical or interventional) or valve replacements may be considered on an emergency basis.

Distributive Shock

This occurs when the afterload is excessively reduced.

Distributive shock can occur in the following situations.

- Septic shock

- Anaphylactic shock

- Neurogenic shock

- Acute adrenal insufficiency.

Septic Shock

Septic Shock Pathophysiology

- Sepsis is the response of the host to bacteraemia/endotoxaemia.

- It may be produced by gram-negative or gram-positive bacteria, viruses, fungi or even protozoal infections.

- Severe sepsis can result in persistent hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation and is called septic shock.

- Local inflammation and substances elaborated from organisms, especially endotoxin, activate neutrophils, monocytes, and tissue macrophages. This results in a cascade of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and other mediators, such as IL-1, IL-8, IL-10, tumour necrosis factor-alpha, prostaglandin E1, endogenous corticosteroids, and catecholamines.

- Effects of this complex mediator cascade include cellular Chemotaxis, endothelial injury, and activation of the coagulation cascade.

Septic Shock Features

- These substances produce low systemic vascular resistance (peripheral vasodilatation) and ventricular dysfunction resulting in persistent hypotension.

- Generalised tissue hypoperfusion may persist despite adequate fluid resuscitation and improvement in cardiac output and blood pressure. This is due to abnormalities in regional and microcirculatory blood flow. These abnormalities may lead to cellular dysfunction, lactic acidosis (anaerobic metabolism) and ultimately, multi-organ failure.

- The early phases of septic shock may produce evidence of volume depletion, such as dry mucous membranes, and cool, clammy skin.

- After resuscitation with fluids, however, the clinical picture is typically more consistent with hyperdynamic shock. This includes tachycardia, bounding pulses with a widened pulse pressure, a hyperdynamic precordium on palpation, and warm extremities.

- Signs of possible infection include fever, localized erythema or tenderness, consolidation on chest examination, abdominal tenderness, guarding, rigidity and meningismus. Signs of end-organ hypoperfusion include tachypnoea, cyanosis, mottling of the skin, digital ischaemia, oliguria, abdominal tenderness, and altered mental status.

- Often, a definitive diagnosis cannot be made on the basis of initial findings on history taking and physical examination and treatment for several possible conditions commence simultaneously.

Septic Shock Treatment

- Removal of the septic focus is an essential step and a priority in the treatment of septic shock, e.g. resection of gangrenous bowels, closure of perforation, and appendicectomy.

- Appropriate antibiotics are necessary to treat the precipitating infection.

- Supportive care: Oxygenation and if necessary, endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation should be administered.

- Intravenous fluids: Restoration of intravascular filling pressures must be done using crystalloids, colloids and blood as necessary. Crystalloids such as isotonic saline or Ringer’s lactate may be used. Large amounts may be required and may contribute to tissue oedema. Colloids restore intravascular volume faster and remain longer in the central circulation. However, they are expensive and are more often used in patients where there is a high risk of pulmonary oedema due to cardiac dysfunction and may not tolerate large volumes of fluids. Blood transfusions may be required to maintain the patient’s haemoglobin levels to 10 gm%.

- Vasoactive agents such as norepinephrine produce vasoconstriction and raise the systemic vascular resistance to normal. Dopamine, dobutamine or adrenaline to increase myocardial contractility may be necessary. Vasopressin as a vasoconstrictor is under trial.

All these potent drugs are given as infusions under careful and continuous monitoring of the blood pressures as well as cardiac filling pressures (central venous pressures, pulmonary capillary wedge pressures). - The role of infusions of sodium bicarbonate and anti-inflammatory mediators has not been found to be helpful.

- Activated Protein C shows some promise as it prevents the release of inflammatory mediators and also prevents/deactivates the action of these mediators on cellular response to inflammation and activation of the coagulation cascade. It is highly expensive and is undergoing trials.

Summary Of Septic Shock

Septic Shock

- Early diagnosis of septic shock

- Empirical antibiotics initially

- Appropriate antibiotics after culture

- Ultrasonography, CT scan and chest X-ray are key investigations

- Treatment of source of infection, for example.

- Pneumonia

- Drainage of pus

- Closure of perforation

- Resection of gangrene

- Aggressive resuscitation, supportive care and close monitoring in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU)

Anaphylactic Shock

Anaphylactic Shock Features

- Occurs on exposure to an allergen the patient is sensitive to. It may be pollen, foodstuffs, preservatives and additives in the food or a medication. The anaphylactic shock that occurs in the hospital is usually due to some drug the patient is allergic to, for example. penicillin allergy.

- The reaction may be in the form of mild rashes with or without bronchospasm or it may be a full-blown anaphylactic shock wherein the patient presents with rashes, generalized oedema including laryngeal oedema, bronchospasm and hypotension and if not treated in time, cardiac arrest.

Anaphylactic Shock Treatment

Anaphylactic Shock Primary

- Oxygen and if necessary, endotracheal intubation and ventilation.

- Adrenaline, 0.5–1 mg IM or 50–100 µg intravenous bolus as necessary to maintain blood pressure.

- Intravenous fluids —isotonic saline or Ringer lactate

- Leg end elevation of bed.

Anaphylactic Shock Secondary

- Chlorpheniramine maleate

- Hydrocortisone 100 mg intravenously

- If facilities exist, take a 10 ml sample of blood to analyse for serum tryptase levels. If raised, they confirm an anaphylactic reaction.

Neurogenic Shock

Neurogenic Shock Causes

- High spinal cord injury

- Vagolytic shock.

Neurogenic Shock Features

Hypotension without tachycardia, may deteriorate to produce shock and cardiac arrest.

Neurogenic Shock Treatment

Intravenous fluids, inotropes and analytics as necessary

Acute Adrenal Insufficiency

Acute Adrenal Insufficiency Causes

An adrenal crisis occurs if the adrenal gland is deteriorating as in:

- Primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease)

- Secondary adrenal insufficiency (pituitary gland injury, compression)

- Inadequately treated adrenal insufficiency.

Acute Adrenal Insufficiency Features

- Headache, profound weakness, fatigue, slow, sluggish, lethargic movement, joint pain

- Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, high fever and chills

- Low blood pressure, dehydration, rapid heart rate and respiratory rate, confusion or coma.

Risk Factors For Adrenal Crisis

- Infection

- Trauma or surgery

- Adrenal gland or pituitary gland injury

- Premature termination of treatment with steroids such as prednisolone or hydrocortisone

Risk Factors For Adrenal Crisis Treatment

- Care of airway, breathing and circulation

- Intravenous fluids

- Hydrocortisone 100–300 mg intravenously

- Treat the precipitating factor

- Antibiotics as necessary.

Obstructive Shock

It can be due to cardiac tamponade or due to tension pneumothorax.

Cardiac Tamponade

Cardiac Tamponade Features

- In obstructive shock, there is impedance to either inflow or outflow of blood into or out of the heart.

- In cardiac tamponade, the pericardium is filled with blood and hampers venous filling as well as outflow.

- The filling pressures of the left-sided and right-sided chambers equalise.

- The central venous pressure is high and the blood pressure is low.

- The patients also have pulsus paradoxus where there is a 10% decrease in systolic blood pressure with inspiration.

Cardiac Tamponade Treatment

- To maintain preload with fluids or blood as indicated.

- Relief of obstruction, drain the pericardial cavity as early as possible.

Tension Pneumothorax

Tension Pneumothorax Causes

- Injury to the lung due to trauma

- Ventilator-induced barotrauma

- Rupture of emphysematous bulla in a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Tension Pneumothorax Features

- Profound cyanosis, distended neck veins

- Tachypnoea, dyspnoea or respiratory arrest

- No air entry on the side of pneumothorax, hyper-resonance to percussion

- Tachycardia, hypotension and cardiac arrest.

Tension Pneumothorax Treatment

A wide (large) bore needle/cannula is to be inserted into the pleural cavity to drain the air. The needle is inserted in the midclavicular line in the 2nd intercostal space on the affected side. This is followed by the insertion of a tube thoracostomy.

Hyperbaric Oxygen

Here, O2 is administered one to two atmospheres above atmospheric pressure in a compression chamber in order to increase the arterial O2 content, mainly the dissolved O2.

Hyperbaric Oxygen Indications

- Carbon monoxide poisoning

- Infections such as tetanus and gas gangrene

- Cancer therapy to potentiate radiotherapy

- Arterial insufficiency

- Decompression sickness and air embolism.

Central Venous Pressure (Cvp)

- One of the essential requirements while treating patients in shock includes monitoring of CVP.

- CVP indicates the volume of blood in the central veins, distensibility and contractibility of the right heart chamber, intrathoracic pressure and intrapericardial pressure. Thus, in shock, measurement of CVP is essential so as to plan for proper fluid management.

Central Venous Pressure Method

- The right internal jugular vein (IJV) is preferred whenever IJV is chosen.

- A 20 cm long IV cannula is introduced into IJV with the patient supine, head down and neck rotated to the opposite side. Head down position helps in engorging the IJV. Seldinger’s technique is employed and the catheter is advanced up to the superior vena cava or right atrium. The patency of the catheter is confirmed by lowering the saline bottle to check the free flow of blood into the connecting tube.

- The tube is connected to the saline manometer and readings of saline level are taken with the “Zero Reference Point” at the midaxillary level in the supine position or at the manubriosternal joint in the semi-reclining position (45°). An electronic pressure transducer may be used for greater accuracy.

Central Venous Pressure Uses

- If CVP is low, venous return should be supplemented by IV infusion, as in cases of hypovolaemic shock.

- When CVP is high, infusion of fluids may result in pulmonary oedema.

- In cardiogenic shock, CVP may be normal or high

Access To Right Heart/Great Veins

- Internal jugular vein

- Subclavian vein

- Median cubital vein

- External jugular vein

Access To Right Heart Complications

- Pneumothorax, haemothorax

- Accidental carotid artery puncture

- Haematoma in the neck

- Air embolism

- Infection.

Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure (Pcwp)

- This is a better indicator of circulatory blood volume and left ventricular function.

- It is measured by a pulmonary artery balloon flotation catheter—Swan Ganz catheter.

Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure Uses of PCWP

- To differentiate between left and right ventricular failure

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Septic shock

- Accurate administration of fluids, inotropic agents and vasodilators.

Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure Method of measuring PCWP

Swan-Ganz catheter is introduced into the right atrium. The catheter has a balloon near its tip. The advancement of the catheter is monitored by watching the pressure tracing. Pressure tracing becomes flat when the balloon gets wedged in a small branch to give capillary pressure. When the balloon is deflated, the pulmonary artery pressure is obtained.

Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure Complications

- Arrhythmias

- Pulmonary infarction

- Pulmonary artery rupture.

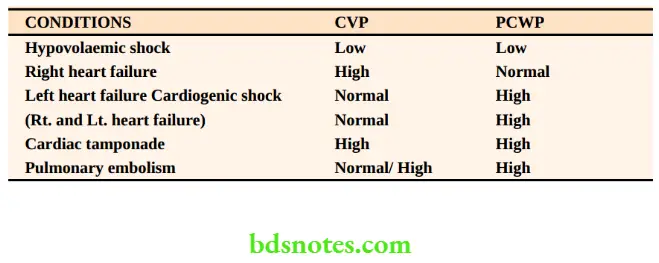

Interpretation In Various Conditions: CVP And PCWP

Note: CVP reflects right atrial pressures only. It may not correlate with left ventricular pressures.

PCWP is a better indicator of left ventricular pressures and is a preferred monitor in cardiogenic shock.

Blood Transfusion Indications for Blood Transfusion

1. To replace acute and major blood loss as in

- Haemorrhagic shock

- Major surgery —open heart surgery, gastrectomy

- Extensive burns

2. To treat anaemia due to

- Chronic blood loss as in haemorrhoids, bleeding disorders, chronic duodenal ulcer, etc.

- Inadequate production as in malignancies, nutritional anaemia.

Although blood transfusion, has several advantages, it is also associated with a multitude of risks. This has led to revised guidelines regarding the threshold for transfusion of blood

Advantages Of Blood Transfusion

- Volume replacement

- ↑O2 carrying capacity

- Replacement of clotting factors

The Revised Guidelines

- Blood loss > 20% of blood volume

- Haemoglobin < 8 g/dL

- Haemoglobin < 10 g/dL in patients with major cardiovascular disease, for example. ischaemic heart disease

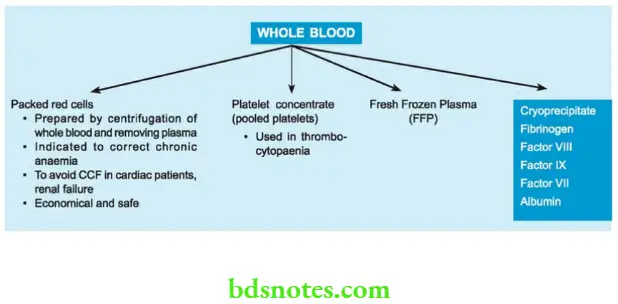

In order to conserve the donated blood and to minimise reactions, it is customary to transfuse blood components rather than whole blood. Hence, packed cells are used to replace oxygen-carrying capacity, platelet concentrates in thrombocytopenia and fresh-frozen plasma for replacement of coagulation factors.

The Following Changes Occur In Stored Blood

- Reduced pH —as low as 6.7–7.0 due to high PCO2

- Increased [K+]—up to 30 mmol/L

- Reduced viability of platelets and leucocytes

- Reduced coagulation factors.

Complications Of Blood Transfusion Immune Complications

Haemolytic Reactions

1. Major (ABO) incompatibility reaction

- This is the result of mismatched blood transfusion.

- The majority of cases are due to technical errors like sampling, labelling, dispatching, etc.

- This causes intravascular haemolysis.

Complications Of Blood Transfusion Immune Complications Clinical features

- Haematuria

- Pain in the loins (bilateral)

- Fever with chills and rigours

- Oliguria is due to the products of mismatched blood transfusion blocking the renal tubules. It results in acute renal tubular necrosis.

Storage Of Blood

Storage Of Blood Preservative

- ACD (Acid – Citrate – Dextrose)

- CPD (Citrate – Phosphate Dextrose)

- CPDA (Citrate – Phosphate-Dextrose Adenine)

- SAGM (Saline – Adenine -Glucose Mannitol)

Storage Of Blood Red cell survival (days)

- 21

- 28

- 35

- 35

Storage Of Blood Treatment

- Stop the blood. Send it to the blood bank and recheck.

- Repeat coagulation profile

- 4 fluids, monitor urine output, check urine for Hb

- Diuresis with furosemide 20–40 mg IV or injection of Mannitol 20% 100 ml IV to flush the kidney.

2. Minor incompatibility reaction

- Occurs due to extravascular haemolysis

- Usually mild, occurs in 2–21 days

- Occurs due to antibodies to minor antigens

- Malaise, jaundice and fever

- Treatment is supportive.

Non-haemolytic Reactions

Febrile reaction

- Occurs due to sensitisation to WBCs or platelets

- Increased temperature—no haemolysis

- Use of a 20–40 mm filter or leucocyte—depleted blood avoids it.

Allergic reaction

- Occur due to allergy to plasma products; manifest as chills, rigours and rashes all over

- They subside with antihistaminics such as chlorpheniramine maleate 10 mg 4

3. Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI)

- It is a rare complication resembling ARDS

- Anti-leucocyte antibodies cause the patient’s white cells to aggregate in the pulmonary circulation

- Treatment similar to ARDS

- Typically remits in 12–48 hours of therapy

4. Congestive cardiac failure (CCF)

CCF can occur if whole blood is transfused rapidly in patients with chronic anaemia.

Storage Of Blood Treatment

- Slow transfusion

- Injection Furosemide 20 mg 4

- Packed cell transfusion is the choice for these patients.

Infectious Complications

Serum hepatitis, AIDS, malaria, and syphilis are dangerous infectious diseases which can be transmitted by blood from one patient to another. The danger is increased in cases of multiple transfusions and in case of emergency situations. “Prevention is better than cure”. Hence, it is mandatory to screen the blood for these diseases before transfusion.

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC)

- Occurs in massive blood transfusion wherein all factors of coagulation are used up resulting in a bleeding disorder.

- It produces severe afibrinogenemia

- It is treated by replacement with fibrinogen (cryoprecipitate) and other clotting factors.

Autologous Transfusion

The concept originated to avoid transfusion reactions which develop when homologous blood is used.

Here patient’s own blood is used.

Massive Blood Transfusion

- > 500 ml over 5 minutes

- > 1/2 the patient’s blood volume in 6 hours.

- > the whole blood volume in 24 hours.

Problems:

-

- Citrate toxicity-hypocalcemia

- Thrombocytopaenia

- Clotting factors deficiency

Types of Autologous Transfusion

1. Predeposit 5 units of blood may be donated over 2–3 weeks before elective surgery.

2. Pre-operative haemodilution: Cases such as surgery for thyrotoxicosis or abdominopelvic resection wherein one can expect 1–2 units of blood loss. Just before surgery, 1–2 units of blood are removed and transfused at the appropriate time.

3. Blood salvage: Blood which was lost during surgery is collected, mixed with an anticoagulant solution, washed and reinfused. This can be done provided surgery does not involve severe infection, bowel resection or malignancy, for example. multinodular goitre.

Autologous Transfusion Advantages

All the risks involved with blood transfusion are avoided.

Autologous Transfusion Disadvantages

- May not be acceptable to the patient

- Sophisticated equipment required

Blood Products

After removal of red cells, the following components may be separated from whole blood:

- Platelets

- Last for 3 to 5 days

- Used with platelet count < 50,000 cells/ mm3

- 6 units increase platelet count by 30–60,000 cells/mm3

- Do not use filters. Use ordinary IV sets.

- Fresh Frozen Plasma

- Indicated in surgeries wherein the patient has severe liver failure.

- After a massive blood transfusion.

- Cryoprecipitate

- Rich source of Factor 8 and fibrinogen

- Used in fibrinogen deficiency, DIC.

- Fibrinogen

- Concentrated from donor pools and rarely used

- High risk of hepatitis.

- Factor 8 and Factor 9 concentrate

- Used in haemophilia and Christmas disease respectively.

- Factor 7 concentrate

- Used in DIC.

Plasma Substitutes

These are colloidal solutions used for the re-establishment of a normal blood volume in emergency situations, for example. polytrauma with severe haemorrhage, massive GI bleed, shock

Clinical Manifestations

- Bleeding from gums

- Bleeding after tooth extraction

- Epistaxis

- Intra-abdominal, retroperitoneal bleeding

- Intracranial haemorrhage

1. Albumin

- It is a rich protein but carries no risk of hepatitis.

- It is available at 4.5% and 20%

- Used in severe burns-acute severe hypoalbuminaemia

- Used in nephrotic syndrome

2. Gelatins

- Good plasma expander

- Plasma expansion lasts a few hours

- Severe reactions with urea—linked gelatin, for example, haemocoel (1:2,000)

- Reactions less with succinylated gelatin, e.g. globulin (1:13,000).

3. Dextrans

- Low molecular weight Dextran 40,000 —(Dextran 40)

- Reduces viscosity and red cell sludging

- May affect renal function and coagulation.

- High molecular weight dextrans (70,000 and 1,10,000 —Dextran 70 and 110)—used rarely.

4. Hydroxyethyl starch

- Derived from starch

- Plasma expansion lasts for over 24 hours

- Maximum dose—15 ml/kg

- Large doses may interfere with coagulation.

- Incidence of severe reactions (1:16,000).

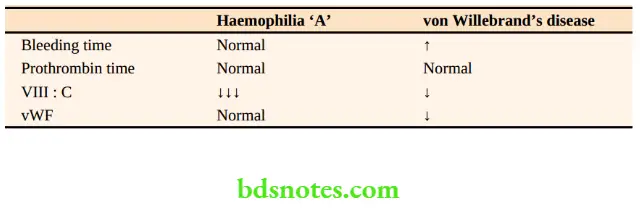

Bleeding Disorders Haemophilia

This is the most common bleeding disorder which occurs due to an X-linked genetic disorder of coagulation.

There are two types:

- Haemophilia A: This results from a reduction of factor 8. (antihaemophilic factor) and is carried by a recessive gene.

- Haemophilia B: This results from a deficiency of factor 9.

Haemophilia A

- Haemophilia ‘A’ occurs in 1 in 5000 male population. Deficiency of factor 8 results in haemophilia A.

- A haemophilic patient’s daughters will be carriers but all his sons will be normal.

- Thus, a carrier woman has a 50% chance of producing a haemophilic male or a female carrier.

- The level of coagulation factor 8 in the blood may be less than 1% of a normal individual.

Clinical features

“Excessive bleeding, unusual bleeding, unexpected bleeding” is due to haemophilia ‘A’.

- Bleeding into joints (haemarthrosis)

- Large joints such as knees, elbows, ankles, and wrists are affected.

- Spontaneous bleeding is common and also due to minor trauma.

- Repeated bleeding may result in permanent damage to the articular surfaces resulting in deformity of the joints.

- Bleeding into muscles

- Calf muscle and psoas muscle haematomas are common resulting in contraction, fibrosis of muscle, muscle pain and weakness of limb.

- Intramuscular injections should be avoided.

Treatment

- Administration of factor VIII concentrate by intravenous infusion is the treatment whenever there is bleeding.

- It should be given twice daily since it has a half-life of 12 hours.

- Any major surgical procedure should be carried out only after raising factor VIII: C levels to 100% preoperatively and maintained above 50% until healing occurs.

- Synthetic vasopressin (DDAVP) produces a rise in factor 8: C.

Causes of death

Cerebral haemorrhage used to be the most common cause of death. However, today HIV

- Infection seems to be the most common cause of death.

- Hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis due to HIV and HCV are the other causes (due to repeated blood transfusions).

Haemophilia B (Christmas disease)

- Incidence: One in 30,000 males. The inheritance and clinical features are identical to haemophilia A.

- It is caused by a deficiency of factor 9.

- Treatment is with factor IX concentrates.

Von Willebrand’s disease (vWD)

- In vWD, there is defective platelet function as well as factor 8: C deficiency and both are due to deficiency or abnormality of vWF.

- Epistaxis, menorrhagia and bleeding following minor trauma or surgery are common.

- Haemarthrosis is rare.

- Treatment is more or less similar to that of mild haemophilia. Thus synthetic vasopressin (DDAVP), or intravenous infusion of factor 8: C or von Willebrand factor concentrates are given to treat bleeding or following surgery.

- Avoid cryoprecipitate for fear of transfusion-transmitted infection.

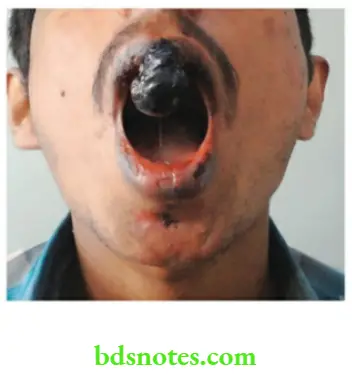

Few Photograph

Leave a Reply